Note

Screenshots may differ slightly depending on software version.

Fractional Factorial with Foldover

Introduction

At the outset of your experimental program you may be tempted to design one comprehensive experiment that includes all known factors - to get the BIG Picture in one shot. This assumes that you can identify all the important factors and their optimal levels. A more efficient, and less risky, approach consists of a sequence of smaller experiments. You can then assess results after each experiment and use what you learn for designing the next experiment. Factors may be dropped or added in mid-stream, and levels evolved to their optimal range.

Highly fractionated experiments make good building blocks for sequential experiments. Many people use Plackett-Burman designs for this purpose, but we prefer the standard two-level approach or the minimum-run (“Min Run”) options offered by Stat-Ease® software. Regardless of your approach, you may be confounded in the interpretation of effects from these low-resolution designs. Of particular concern, main effects may be aliased with plausible two-factor interactions. If this occurs, you might be able to eliminate the confounding by running further experiments using a foldover design. This technique adds further fractions to the original design matrix.

We will discuss foldover designs that offer the ability to:

free main effects from two-factor interactions, or

de-alias a main effect and all of its two-factor interactions from other main effects and two-factor interactions.

Stat-Ease software’s “Foldover” feature automatically generates the additional design points needed for either type of design augmentation.

Saturated Design Example

Lance Legstrong has one week to fine-tune his bicycle before the early-bird Spring meet. He decides to test seven factors in only eight runs around the quarter-mile track. We show Lance’s design below, which can be set up from Stat-Ease software via its factorial tab with the default design builder for a “2-Level Factorial”. It is “saturated” with factors, that is, no more can be added for the given number of runs. (Inspiration for this case study came from Statistics for Experimenters, 2nd Edition (Wiley, 2005) by Box, Hunter and Hunter (“BHH”). In Section 6.5, BHH reports a very similar study with a few factors and results differing from those shown below.)

“When your television set misbehaves, you may discover that a kick in the right place often fixes the problem, at least temporarily. However, for a long-term solution the reason for the fault must be discovered. In general, problems can be fixed or they may be solved. Experimental design catalyzes both fixing and solving.” – Box, Hunter and Hunter.

Experimental design and results

As you will see in a moment via an evaluation, this is a resolution III design in which all main effects are confounded with two-factor interactions. (To alert users about these low-resolution designs, they are red-flagged in the design builder within Stat-Ease software.)

Two-level factorial design builder

Lance would prefer to run a resolution V or higher experiment, which would give clear estimates of main effects and their two-factor interactions. Unfortunately, at the very least this would require 30 runs via the “min-run Res V” design (also known as “MR5”) invented by Stat-Ease statisticians. But 30 runs are too many for the short time remaining before competition. Lance briefly considers choosing an intermediate resolution IV design (color-coded a cautionary yellow in Stat-Ease), but seeing that it requires 16 runs, he decides to perform only the 8 runs needed to achieve the lesser resolution III.

To save time, load the experimental results by clicking Help, Tutorial Data -> Biker. After looking over the data, check out the alias structure of the design by clicking the Evaluation node on the left. Note that Stat-Ease recognizes that this meager design can only model response(s) to the order of main effects. The program is set to produce results showing aliasing up to two-factor interactions (2FI) – ignoring terms of 3FI or more.

Evaluating the biker’s experiment

Now press the Results button at the top of the data window, and then the Factorial Effects Aliases tab to see the impact of only running a Res III design in this case.

Alias structure for first block of biking time-trials

This design is a 1/16th fraction, so every effect will be aliased with 15 other effects, most of which are ignored by default to avoid unnecessary screen clutter. The output indicates that each main effect will be confounded with three two-factor interactions.

Don’t bother studying the remaining design evaluation report. Click the Time ¼ mile node in the analysis branch at the left and press the Start Analysis button to bring up the Effects window. Notice that there are three effects that stand off to the right of the line of trivial effects near zero. Starting from the right, click those three largest effects (or rope them off as pictured below).

Effect graph - three largest ones selected

Then on the Pareto plot, right-click the biggest bar (E) to show its aliases as below.

Pareto chart of effects with aliases displayed for the bar labeled “E”

Factors B (Tires), E (Gear), and G (Generator) are clearly significant. Click ANOVA to test this statistically. Before you can go there, you are reminded via the warning shown below that this design is aliased.

Alias warning

You know about this from the design evaluation, so click No to continue. (Option: click Yes to go back and see the list. Then click the ANOVA button.)

ANOVA output

Lance gets a great fit to his data. Based on the negative coefficient for factor B, it seems that hard tires decrease his time around the track. On the other hand, the positive coefficients for factors E and G indicate that high gear gives him better speed and the generator should be left off. The whole approach looks very scientific and definitive. In fact, after adjusting his bicycle according to the results of the experiment, Lance goes out and wins his race!

However, Lance’s friend (and personal coach) Sheryl Songbird spots a fallacy in the conclusions. She points out that all the main effects in this design are confounded with two-factor interactions. Maybe one of those confounded interactions is actually what’s important. “You must run at least one more experiment to clear this up,” says Sheryl. “That sounds like a great idea,” says Lance tiredly, realizing that he will never sleep easy knowing that some doubt remains as to the ideal settings for his bike.

Complete Foldover Design

To untangle the main effects from the interactions in his initial resolution III design, Lance can run a “foldover,” which requires a reversal in all of the signs on the original eight runs. Combining both blocks of runs produces a resolution IV design – all main effects will be free and clear of two-factor interactions (2FI’s). However, all the 2FI’s remain confounded with each other.

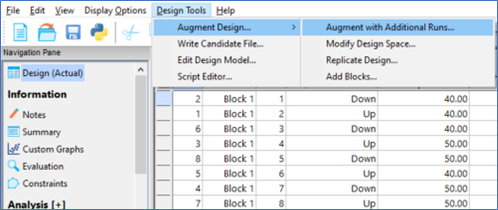

To create the new runs for the foldover, click the Design node and then select Design Tools, Augment Design, Augment with Additional Runs.

Augment the first block of runs

This selection brings up the following screen.

Foldover option suggested by default

The default suggestion by Stat-Ease software for Foldover is good, so click OK to continue. The program now lists which factors to be folded over. By default, Stat-Ease software selects all the factors. This represents a complete foldover. Factors can be selected or cleared with a right click on the factor, or by double-clicking on the factor.

Choice of factors to fold over

In this case, it is best that all factors be folded over, so click OK to continue. The program displays the following warning (really just a suggestion).

Suggestion to evaluate foldover design

Click Yes and go to Design Evaluation.

Press Results and Factorial Effects Aliases to see the augmented design evaluation – much better!

Aliasing after foldover

Complete foldover of a resolution III design results in a resolution IV design. The proof for this case is that the main effects are now aliased only with three-factor interactions – ignored by default because they are so unlikely. See Montgomery’s Design and Analysis of Experiments textbook for the details on why this happens. By the way, the power also increases due to the doubling of experimental runs. If you’d like to assess this, go back to the Model screen and change the Process Order to Main Effects before re-computing the Results. Then press the Model Terms button.

Now return to the main Design node and select View, Display Columns, Sort, Std Order, Ascending. (Tip: A quicker route to sorting any column is via a double-click on the header.) Notice how each run in block two is the reverse of block one. For example, whereas the seat (factor A) went up, down… in block 1, it goes down, up… in block 2 – everything goes opposite.

Folded-over design in standard order

Lance’s results for the additional runs appear in the following table.

Experimental results for foldover block

To continue following along with Lance, within your Response 1 column, enter his above times for the foldover block (Block 2) of eight runs, as shown below. First be sure you have changed the design matrix to standard order. Input factors must match up with the responses, otherwise the analysis is nonsense.

Folded-over design in standard order with block 2 times (secs) keyed in

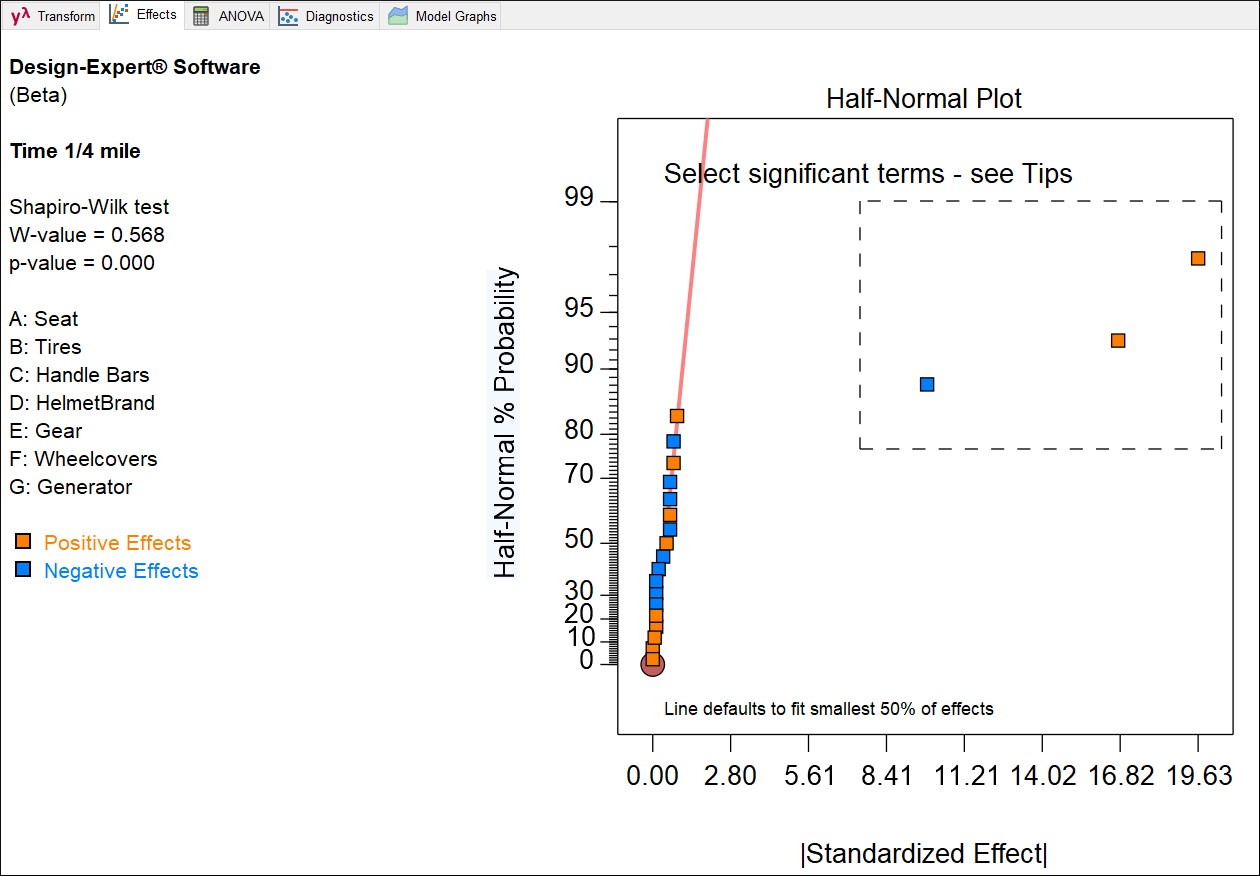

When you complete the data entry for Block 2, save your work via File, Save As…. When prompted, go to the folder of your choice and type in a new File name, such a “biker-foldover”. Then, click the Time ¼ mile node and press the Start Analysis button to display the Effects plot. Starting from the right, click the three largest effects.

Half-normal plot of effects after foldover

It now appears that what looked to be effect G really must be AF. Be careful though – recall from the design evaluation that AF is aliased with BE and CD in this folded over design. (To see this, you can go back and look at the screen shot from before or press Evaluation on your screen and look at the Report. Or, even better, just right click on AF on the Half-Normal Plot (as pictured above)). Stat-Ease software picks AF only because it is the lowest in alphabetical order of all the aliased terms.

From their subject matter knowledge, Lance and Sheryl know that AF, the interaction of the seat position with the wheel covers, cannot occur; and CD, the interaction of handle bar position with the brand of helmet, should not exist. They are sure the only feasible interaction is BE, the interaction of tire pressure and gears. However, proceed with the ANOVA on the model with the two-factor interaction at the default of AF.

The software gives the following warning about model hierarchy.

Warning that model is not hierarchical

Because you selected interaction AF, the parent factors A and F must be included in the model to preserve hierarchy. This makes the model mathematically complete. Click Yes to correct the model for hierarchy.

Hierarchy corrected

Notice that these two new model terms, A and F, fall in the trivial-many near-zero population of effects. Therefore you may find that one or both are not very significant statistically. Nevertheless, it is important to carry them along.

Press forward to ANOVA again. You are now warned that “This design contains aliased terms. Do you want to switch to the View, Alias list…?” Click No to continue. (You will return later to this Alias List, so don’t worry.)

The ANOVA looks good. (Factor A is not significant but it’s in the model to preserve hierarchy.)

ANOVA output after foldover

Click Diagnostics. You will see nothing abnormal here. Then click Model Graphs to view the “AF” interaction plot. Because neither “A” nor “F” as main effects changes the response very much, the interaction forms an X, as shown below.

The AF interaction plot

Keep in mind that Lance and Sheryl know this interaction of the seat position with the wheel covers really cannot occur, so what’s shown on the graph is not applicable.

Investigation of Aliased Interactions

Lance decides to investigate the other, more plausible, interactions aliased with AF. You can follow along on your computer to see how this works. Lance clicks back onto the Effects tab, then selects the Numeric tab and maximizes this window.

Viewing the alias list

He locates and right clicks term AF, below left, then selects BE, resulting in the next screenshot shown.

Substituting BE for AF (before)

Substituting BE for AF (after)

Note that this action is reversible, that is, AF can be substituted back in for BE. But for now, just to do something different, Lance selects the Pareto tab. The effects of A and F remain from the prior model in hierarchical support of the AF interaction.

Pareto chart with BE substituted for AF

Now with interaction BE as the substitute, these two main effects, clearly insignificant, are no longer needed, so click the bars labeled “F” (ranked 4th) and “A” (6th) to turn off these vestigial model terms. Notice how this simplifies into a family of effects: B, E and BE. In other words, this model achieves hierarchy with all terms being significant on an individual basis. As a general rule, a simpler (or as statisticians say, “more parsimonious”) model like this should be favored over one that requires more terms. This is especially true for models with parent terms that are not significant on their own, such as the one you created earlier with the orphan AF.

Lance now displays the BE interaction. Take a look at it yourself by clicking the Model Graphs button. (Click No if advised to view aliased interactions.)

The BE interaction plot (effect of tires at low versus high gear)

Lance feels that it really makes much better sense this way.

Notice that Stat-Ease software displays a red point on the graph, which in fractional factorials, only appears under certain conditions. Click it to identify these conditions.

Actual experimental run identified (enlarged circle)

At the left of the graph you now see that at this point the tire pressure (B) equals 40 psi and the gear (E) is set high. Above that you see the run number identified (yours may differ due to randomization) and the actual time of 83 seconds. The other factors, not displayed on the graph, would normally default to their average levels, but because they are categorical, the software arbitrarily chooses their low levels (red slide bars to the left). This setup matches the last row of the foldover in standard order.

If you prefer to display the results as an average of the low and high levels, click the list arrow on the floating Factors Tool and make Average your selection, as shown below (already done for factors A:Seat, C:Handle Bars, D:Helmet Brand, F:Wheelcovers, and G:Generator).

Changing to average levels for factors not displayed in the interaction

Notice that the point on the graph now disappears because the average seat height was not one of the levels actually tested. To return the interaction plot back to original settings, press Default on the Factors Tool. Then play with the other settings. See if you can find any other conditions at which an actual run was performed. Remember that even with the foldover, you’ve only run 16 out of the possible 128 (27) combinations, so you won’t see very many points, if any, on the graphs. For example, as shown below, one of the other actual points (the green circle) can be found with the factors set on the tool as shown below (G:Generator switched from Off to On).

Another actual point display by re-setting G: Generator to its high level

Just to cover all bases, Lance decides to look at the second alias for AF – the CD effect, even though it just doesn’t make sense that C (handlebars) and D (helmet brand) would interact. Lance sees that the interaction plots look quite different. What a surprise! If you can spare the time, check this out by going back to the Effects button and selecting Numeric from the selection tool. Then replace BE with CD via the right-click menu. (You must then select the factors C and D in the model to make it hierarchical.) Based on his knowledge of biking, Lance makes a “leap of faith” decision: He assumes that BE is the real effect, not CD.

Now would be a good time to save your work on the analysis by clicking the disk icon ![]() .

.

Inspired by these exciting results, Lance begins work on a letter advising the bicycle supplier to change how they initially set them up for racers. However, Lance’s friend and personal coach, Sheryl, reminds him that due to the aliasing of two-factor interactions, they still have not proven their theory about the combined impact of tire pressure and gear setting. “You must run a third experiment to confirm the BE interaction effect,” admonishes Sheryl. “I suppose I must,” replies Lance resignedly.

Single Factor Semi-Foldover

Sheryl declares, “By making just eight more runs you can prove your assumption.” “Wonderful,” sighs Lance as he rolls his eyes, “Please show me how.” “Well,” replies Sheryl, “If you run the same points as in the first two experimental blocks, but reverse the pattern only for the B factor, then B and all of its two-factor interactions will be free and clear of any other two-factor interactions.” “But that requires 16 more runs,” Lance complains. “Hold on,” says Sheryl, “I saw an article posted by Stat-Ease on How To Save Runs, Yet Reveal Breakthrough Interactions, By Doing Only A Semifoldover On Medium-Resolution Screening Designs. It details how you can do only half the foldover and still accomplish the objective for de-aliasing a 2FI.” Thus, Lance allows himself to be cajoled into another eight times around the track.

You can create the extra runs by returning to the Design node and from there selecting Design Tools, Augment Design, Augment with Additional Runs. The program now advises you do the Semifold.

Augmenting via semifold

Press OK to bring up the dialog box for specifying which runs will be added in what now will become a third block of runs for Lance to ride. Before proceeding, read the advice provided on the various choices you must make. In the field for Choose the factor to fold on, select B to de-alias the highly likely BE interaction from AF and CD and settle this confounded relationship once and for all. Lance and Sheryl puzzle over the next question, Choose the factor and its level to retain. According to the advice on screen, a good choice might be E+, that is, the high gear, which significantly speeds up the bike when tire pressures are high. However, they settle on D+ because Sheryl likes the look of Lance wearing this brand of helmet—the Windy. For the primary purpose of the semifold—dealiasing a 2FI—the choice of factor and its level to retain makes no difference, so why not go for something stylish! (If you are a doubter, try E+ versus D+ and other choices to see if BE becomes de-aliased in any case.)

Specifying the semifold

Give this the OK, click Yes as advised to go to design evaluation. You should now see the starting screen for Evaluation – press Results and then Factorial Effects Aliases* to see the improvement in resolution of the BE interaction. Scroll down to view the 2FIs and notice that BE is now aliased only with three-factor interactions.

Aliasing after the semifold

Notice that some effects, for example AB, are partially aliased with other effects. This is an offshoot of the semifold, causing the overall design to become non-orthogonal; that is, effects no longer can be independently estimated. You will see a repercussion of this when analyzing the data.

Click the main Design branch to see the augmented runs. Then double-click the Std column header to get it back in standard order.

Lance’s results can be seen in the following table.

Experimental results for third block (semifold)

Enter the times shown above into your blank response fields. Again, be certain everything matches properly. Now, save your work via File, Save As…. When prompted, go to the folder of your choice and type in a new File name, such as “biker-semifold”. Then go to the Time ¼ Mile node on the left and press the Start Analysis button. The following warning comes up that the design is not orthogonal (as explained a bit earlier).

Warning about semifold not being orthogonal

Press OK. Then, rope the three largest effects as pictured below. You will find B, E, and interaction BE to be significant.

Half-normal plot after semifold

The effects shift – you may not notice the change when all are selected at once.

When you press ANOVA, the “This design contains aliased terms” warning again appears. Click Yes to see the alias list, which now looks much better than before: The model (“M”) terms are aliased only with high-order interactions that are very unlikely to have any impact on the response.

Alias list brought up by software

Click ANOVA again and review the results. Then move on to Diagnostics. Check out the Normal Plot of Residuals and Resid. vs Run graphs. They look normal—that is good! (Notice that the Box-Cox plot now recommends a Square Root transformation. If you are not completely worn out at this point, go back to the Analysis [+] node at the left and create an alternative model by going from No Transform to Square Root. Then re-analyze. If you do so, a comparison of the statistics and graphs shows only a very slight improvement that makes no difference to the overall outcome—hardly worth the bother.) Press ahead to Model Graphs. The interaction plot of BE looks the same as before. Check it out. Just to put a different perspective on things, on the Factors Tool, right click E: Gear and select it for the X1 axis. You now get a plot of EB, rather than BE. In other words, the axes are flipped. Note that the lines are now dotted to signify that gear is a categorical factor (high or low). On the BE plot the lines were solid because B (tire pressure) is a numerical factor, which can be adjusted to any level between the low and high extremes.

Setting E:Gear to the X1 axis

In this case, you will do well by reverting the BE plot back to the original layout by right-clicking over B:Tires and putting it back on the X axis. This puts the continuous factor on the continuous axis and the categorical above as two non-numerical levels, which is more informative. Furthermore, putting Gear on the X axis exposes a non-intuitive setting of its levels as High at the minus level and Low at the plus level.

Interaction BE with gear chosen for X1 axis

Conclusion

“Thank goodness for designed experiments!” exclaims Lance. “I know now that if I am in low gear then it doesn’t matter much what my tire pressure is, but if I am in high gear then I could improve my time with higher tire pressure.”

“Or,” cautions Sheryl, “You could say that at low tire pressure it doesn’t really matter what gear you are in, but at high pressure you had better be in high gear!”

“Whatever,” moans Lance.

“Another thing I noticed,” prods Sheryl, “Your average time for each set of eight runs increased a lot. It was 70 seconds in the first experiment, 80 in the second set and almost 85 seconds in the last set of runs. You must have been getting tired. It’s a good thing we could extract the block effect or we might have been misled in our conclusions.”

“It doesn’t get any better than DOE,” agrees Lance.

In this instance, by careful augmentation of the saturated design through the foldover techniques as suggested by Stat-Ease (defaults provided via augmentation tool), Lance quickly found the significant factors among the seven he started with, and he pinned down how they interacted. He needed only 24 runs in total – broken down into three blocks. A more conservative approach would be to start with a Resolution V design, where all main effects and two-factor interactions would be free from other main effects and two-factor interactions. But this would have required 30 experimental runs at the least with the MR5 design (offered only by Stat-Ease!), or far more (64) with the standard, classical two-level fractional factorial design (27-1). And lest you forget, Lance Legstrong may not have won the early-bird Spring meet without the results from his first eight-run experiment.

In this case, Lance discovered a winning combination with the saturated Resolution III design. Thus, he developed a fix for the problem via design of experiments. However, without the prompting of Sheryl Songbird, his friend and personal coach, Lance may not have done the necessary follow up experiments via foldover to determine exactly what caused the improvement. She helped him use DOE to solve the problem.